What it is

Back pain is most commonly of mechanical nature, meaning coming from how we move and use our body. If your back-pain changes — for better or worse — with varying movement and positions accompanied by stiffness or loss of normal motion, you likely suffer from mechanical back pain. Back pain can be coming from muscle, facet joint, nerve, disc, referral from another location, chemical irritation, and more. Treatment for each is different, which illustrates the importance of making an accurate diagnosis. There is no such thing as “nonspecific” low back pain or a one-size-fits-all treatment protocol.

The exact source of back pain is one of the most difficult diagnoses to make, if done correctly. An example? Many avid golfers come in with chronic back pain. A very common cause? Lack of hip mobility causing the low back to excessively twist and turn during swinging, leading to hypermobility and instability in the lower spine. Without a thorough assessment, a clinician could “chase the pain,” start adjusting the spine where it hurts, causing more movement, exacerbating the current problem and leading to a worsening of pain. At Nexus Spine & Sport, Dr. Annas takes the time to find the true cause of pain, and tailor care towards the individual patient.

The more common, acute back pain is an episode lasting no longer than six weeks. Back pain is considered chronic when lasting greater than three months.

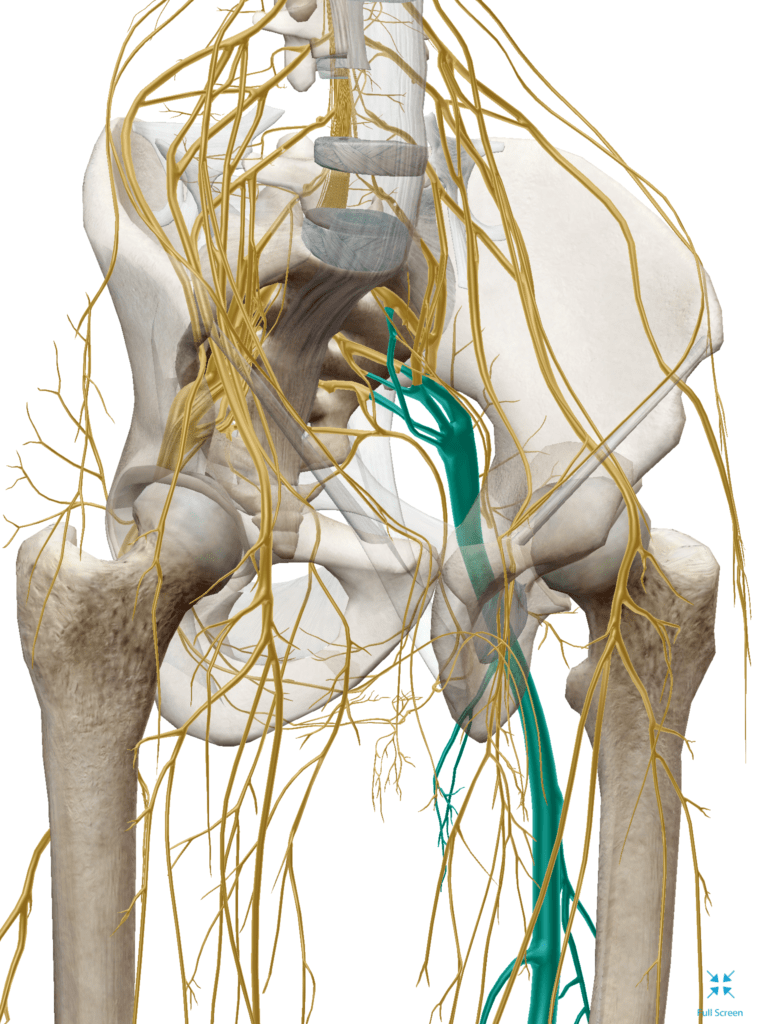

The nerve supply to your legs stems from the spinal cord within the spine. Poor spinal mechanics and joint movement can alter the way the muscles of the legs and pelvis function, perpetuating pain and poor mechanics, and vice versa. This can hinder the ability of the muscles to function, which impacts the way the surrounding joints move. Sound like a circle? It’s because it is. Chronically tight and spastic muscles can impact the health of the joints and ligaments. Proper movement is vital for joints to receive nourishment and stay healthy. It is not uncommon to experience symptoms such as pain, muscle weakness, or numbness and tingling anywhere down your leg(s), with or without local back symptoms!

In rare cases, back pain can be non-mechanical in nature and be indicative of something more serious. Although rare, it is possible and Dr. Annas will make sure you have the necessary referral immediately and collaborate with your primary care provider.

Because back pain is incredibly complex and multifactorial, a through patient history and examination is critical in order for the clinician to understand the problem.

What it isn’t

The pain we feel is simply a request from our brain to change. Pain is usually unassociated with damage, rather it’s an alert we need to change our physical behavior or else serious problem may result.

Mechanical back pain does not have to be debilitating and just because you have back pain does not mean you’re broken, needing to be “fixed”.

Just because you have pain doesn’t mean you need an MRI; just because your MRI shows “degeneration,” “disc bulges,” or “arthritis,” doesn’t mean it’s causing your pain. Back pain is often unassociated with aforementioned structural changes commonly found from imaging, e.g. X-ray, CT scan, MRI. These diagnoses are present in a large percentage of completely asymptomatic people! Including elite athletes. Your pain and dysfunction are likely from another source. Furthermore, there’s a high prevalence of interpretive errors between radiologists. So, not only does imaging your spine result in a high rate of unrelated findings, the professionals interpreting them cannot concisely agree upon diagnoses!

Another interesting phenomenon is that of disc herniations, and their vast prevalence in ASYMPTOMATIC patients! This article HERE highlights the percentages of people with disc herniations and no symptoms, and how the percentage increases as we age. People often come to us saying “My back hurts because I have a disc herniation” Which definitely may be the case at that instant, but this isn’t a reason for you tolerate pain as being acceptable. Conservative care is an effective method of managing this condition in most cases. After an exam, we will determine if surgical consult or other referral is deemed necessary, and the appropriate calls will be made.

A final consideration is what this article HERE discusses, and how disc bulges can actually resorb themselves with time! We are here to help expedite that process and ease the back pain, leg pain, or hip pain that may accompany the healing process. Get your case looked at by an expert! Track any bowel, bladder, incontinence, sensory changes especially after a trauma as this can be a serious condition. If